British actor Terence Stamp is in the news once again in relation to a sequel to another film to be shot in Australia as well as locations beyond these shores.

So, it seemed appropriate to share a little more about the actor, the film that gave him his brilliant cinematic career and the Australian Director of Photography who played a role in helping him get there with his very first part, something of a minor miracle.

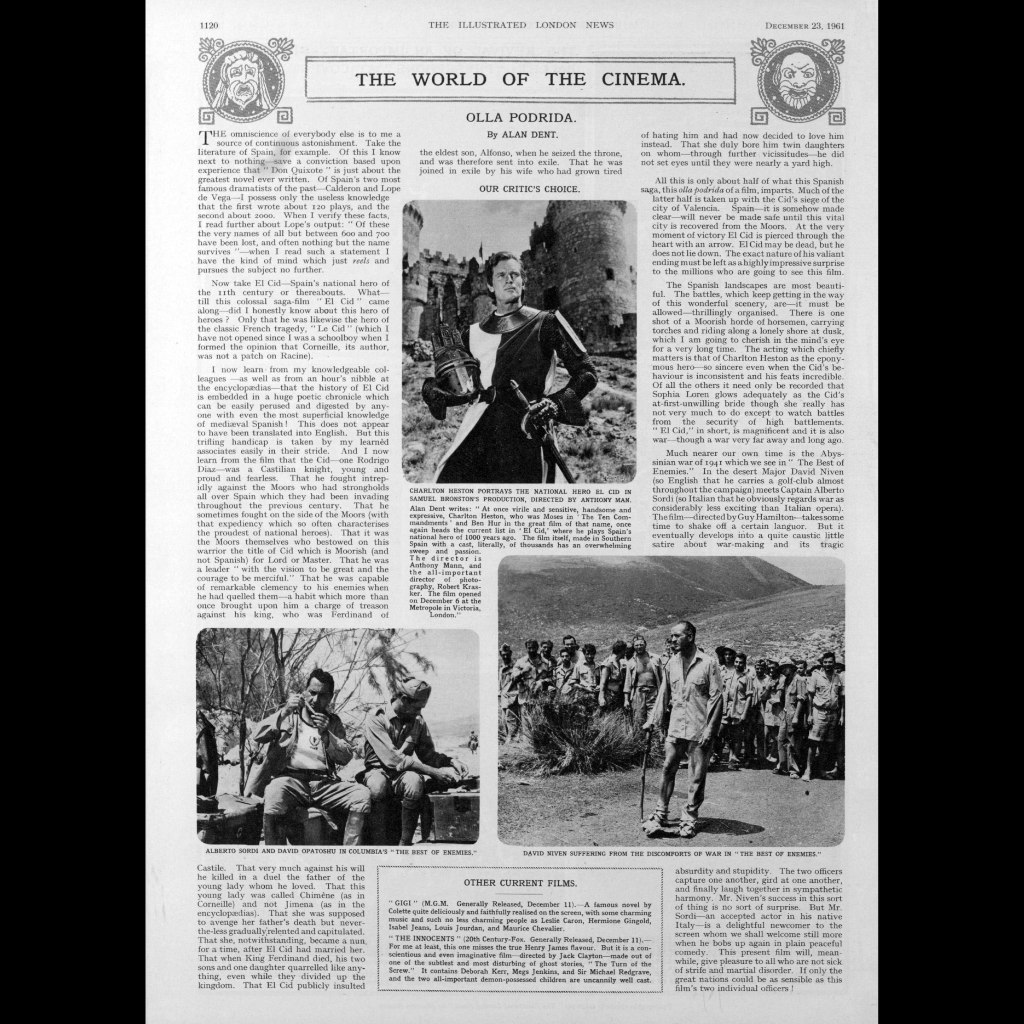

Billy Budd was a departure for Robert Krasker from the Technicolor widescreen epics that late 1950s and early 1960s Hollywood believed would persuade its formerly dedicated movie audiences to tear themselves away from their television screens.

“Robert Krasker, Ustinov’s cinematographer, was a legend who ranged from epic comedies like Caesar and Cleopatra to classic dramas like Brief Encounter.”

Krasker began his filmmaking career at Les Studios Paramount in the south-eastern Parisian suburb of Joinville-le-Pont with three remakes of a US Paramount Pictures film, with all versions in black and white or, as it was often referred to in Europe, monochrome.

His first few projects at Alexander Korda’s London Film Productions where he was apprenticed to French Director of Photography Georges Périnal were in monochrome, too, but DoP and apprentice-cum-camera operator both earned their stripes as colour cinematographers when Korda made a deal with Technicolor to site its British processing and printing laboratory onsite at his Denham Studios complex in Buckinghamshire west of London.

After Krasker became a Director of Photography in his own right, his first few projects were shot in black and white but the big breakthrough that led to him being hailed as “The Man for Colour” came with DoPing Henry V for actor/director Laurence Olivier.

From then onwards Robert Krasker would jump between the two forms, monochrome and colour, as story and budget required, and Billy Budd did not have budget enough for Technicolor.

A well-matched unit, Krasker and Ustinov

Peter Ustinov was well-suited to tackling a war film about characters with ambiguous motivations, according to Michael Sragow:

In many ways, Ustinov was in his wheelhouse—he was part of a generation of veterans. During his British Army service in World War II, he had collaborated with thriller-writer Eric Ambler and the great director Carol Reed (best known for Odd Man Out and The Third Man, both shot by Krasker) on the famous propaganda feature The Way Ahead, which dramatized a lieutenant (David Niven) molding conscripts into a fighting unit. Ustinov himself despised being in the army: he called it “a nightmare school for backward adults, in which degrees could be achieved in monstrous disciplines.”

Krasker (underclass) and Ustinov (upperclass) intimately understood the true nature of the British Empire’s class system and its expressions and impositions through architecture, clothing and space:

What sustains the film’s suspense is its piquant clarity about the everyday dangers of an eighteenth century sailor’s life (an exotic extra for today’s audiences, now that Tall Ship adventures are no longer a popular genre). Ustinov and Krasker exploit nautical space to brew up an enveloping aura. They convey the emotional and physical dynamics of every onboard experience, from the sailors sleeping on hammocks in close quarters to the vertiginous loneliness and fear of a foretopman climbing the foremast. Their visual limpidity enables us to “read” the class bias built into the architecture of the ship, from the quarter deck down to the hold, as easily as we do the gaps between upstairs and downstairs on Upstairs, Downstairs or Downton Abbey.

Links

- American Cinematographer – Summary of Current Wide-Screen Processes – originally published in November 1955 and reprinted on 3 April 2020

- in70mm.com – Introduction of CinemaScope

- Sight and Sound – A wider view: CinemaScope today – 21 August 2019

- widescreenmuseum.com – CinemaScope: What is it, how it works

- Wikipedia – Billy Budd (film)

- Wikipedia – CinemaScope

- Wikipedia – Michael Sragow

- Wikipedia – Peter Ustinov